The Spanish Revolt: defying the crisis from below

Present and Possible Future(s) of the 15M Movement

“The sun has risen!” – popular slogan of the Spanish Indignados

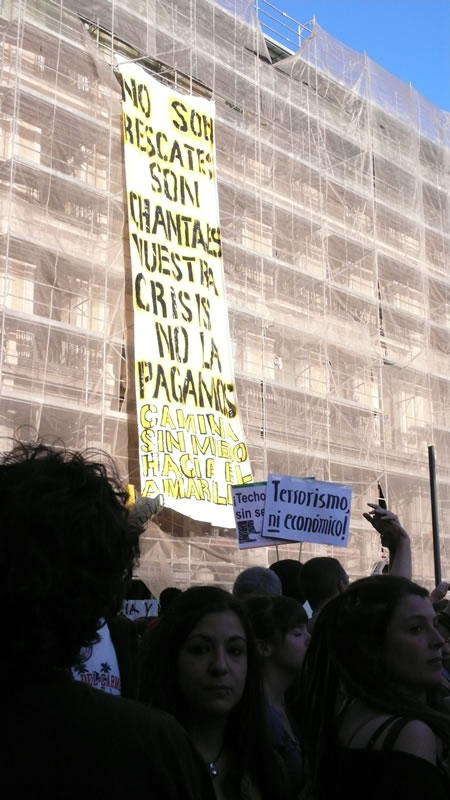

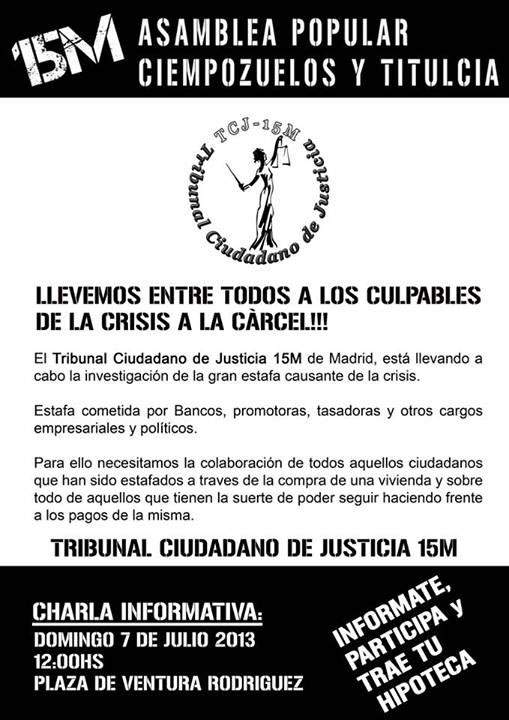

The subprime mortgage crisis in the USA in August 2007 triggered the end of the Spanish property bubble (1997-2007), initiating a process of economic convulsion and collective dispossession in Spain. To deal with the economic disaster, the PSOE Government (Spanish Socialist Workers’ Party), pushed by the European Central Bank (ECB), the European Union (EU) and the International Monetary Fund (IMF), began re-capitalizing the banks and financial institutions hit by the crisis. But the crisis could not be contained: the Spanish economy – and the so called ‘Spanish miracle’- had been based on an abnormal growth in property prices, household debt and the easy flow of credit. The subsequent contraction of credit put an end to Spanish society’s artificial dreams. Following the public bail-out of several banks, the PSOE Government implemented austerity measures with one main objective: to save the national banking structure at all costs, despite Spanish sovereign debt with the ECB and the inhumane destruction of social rights (now reformulated as ‘excessive spending’). The consequences of the austerity measures are well known in the southern countries of Europe: the rescinding of workers rights, the compression of wages, privatization of public health care, destruction of social services and enormous unemployment rates. Finally, on May 15th 2011, a wide popular protest erupted in Madrid, the capital city of Spain, to contest this neoliberal rule. These protests were different from previous ones, they were special: they started a new wave of collective struggle and solidarity unparalleled in the short history of Spanish democracy.

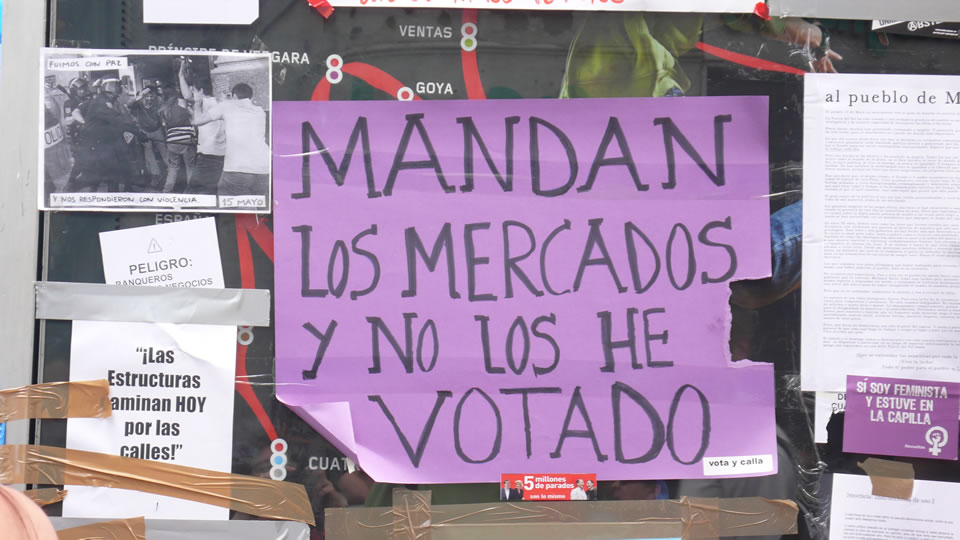

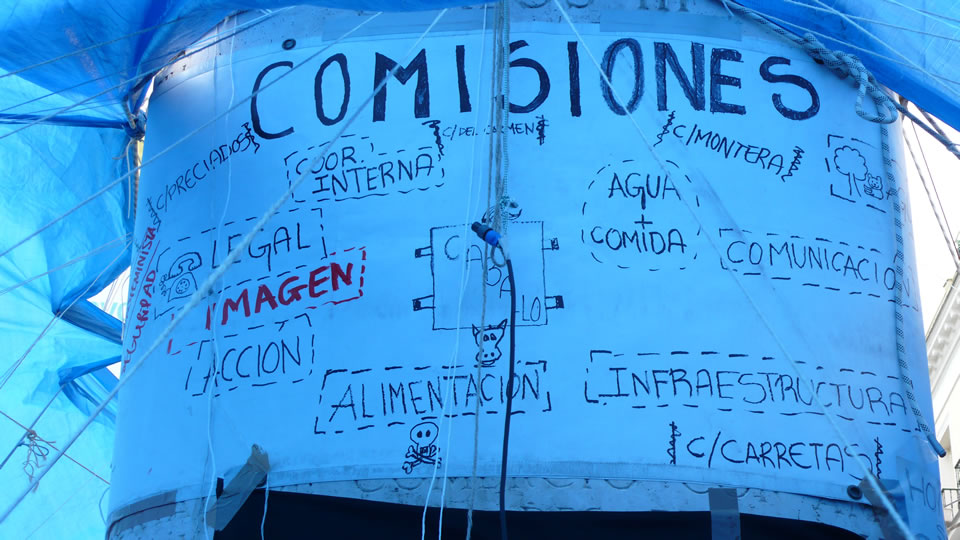

What became known as the ‘15M’ demonstrations ignited a process of re-politicization of the public sphere: the following day, several generations of Spaniards went again – as a multitude – to the ‘Puerta del Sol’, the center square of Madrid, occupying the place with an assembly. A democratic, plural and critical spirit started to emerge from the center of the city itself, generating a singular urban paradox: the popular reclaiming of the commercial zone of the capital city. Soon the general assembly divided itself into different assemblies and working groups (culture, economy, education, respect, short-term politics, long-term politics, etc.) and the people decided to build a permanent encampment in the square, called Acampada Sol (Sun encampment). The occupation of Sol lasted for almost one month, a period in which all people – from day to night – could take part in different working groups or commissions, since they were open to anyone who strolled through the center of Madrid. The inclusive logic of the the 15M Indignados, its plural articulation of antagonism, generated a common sense against the austerity measures, the corruption of the major parties of Spain (PSOE, PP) and the limits of the liberal democracy. Over the course of one month, people with different ideologies and from distinct social strata discussed the principal problems in Spain. Producing consensus between all the participants was not an easy task. Nevertheless, the pacifist, leftist and heterogeneous character of the 15M Movement – full of hopes and contradictions – allowed the movement to win the affection of the majority of Spaniards (despite the attacks of all the media, from the left to the right).

After the first month, Acampada Sol disappeared from the center of Madrid, transforming itself into a web of interconnected assemblies disseminated throughout the Spanish geography: local assemblies in the municipalities (rural or semi-rural environments), district assemblies in the cities (urban environments). Furthermore, there were periodic assemblies in different zones and, occasionally, general assemblies in the capital cities of each province. The movement started to grow and expand. Five elements were decisive in this process of expansion:

1) The autonomous production of independent information (critique, knowledge, research) and its diffusion thanks to the internet, Facebook, Twitter and the blogosphere.

2) The visibilization of antagonism and social conflict through periodic assemblies in the public squares (and the open and inclusive character of these meetings that allowed the movement to accommodate social actors with different ideologies, distinct ethnicities and across generations).

3) The radical criticism of Spain’s political and economic structure, including political parties, major trade unions, corruption and the passivity of the population (that is to say, a non-institutional way of constructing the antagonism from the left).

4) The common production of an innovative protest culture, with a singular vocabulary, new political grammar and focused on horizontal and democratic organization.

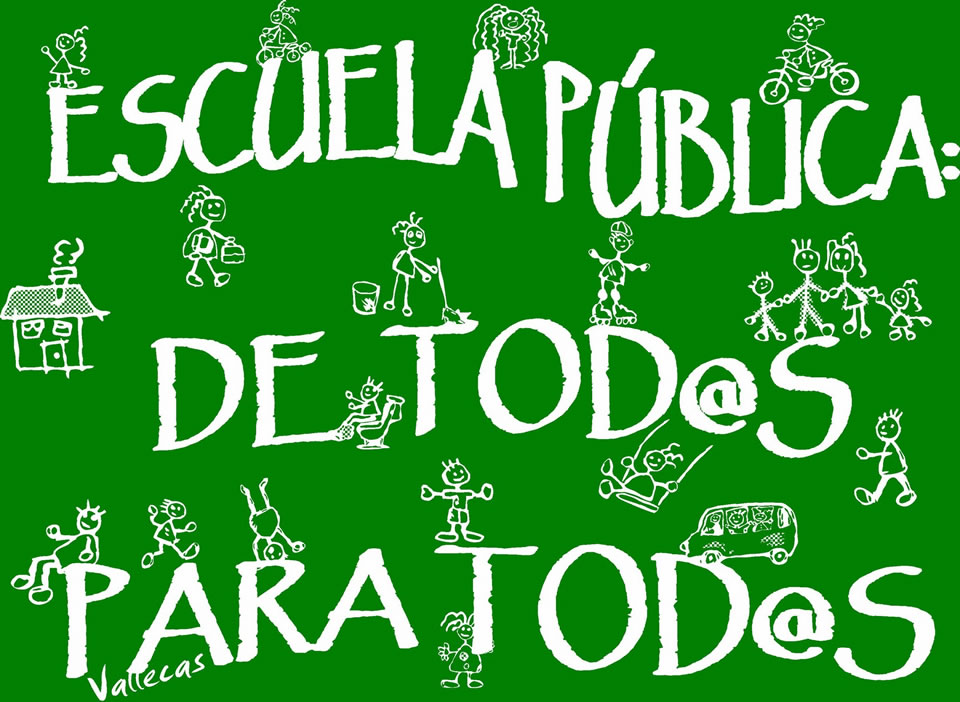

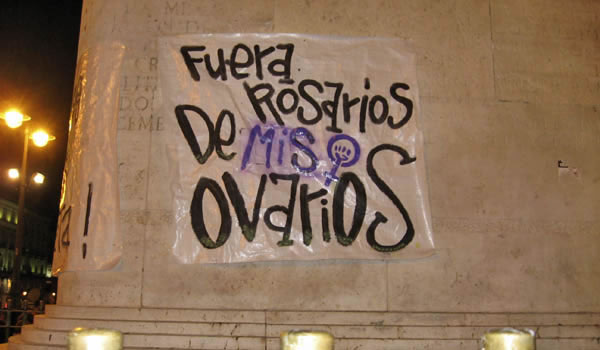

5) The transversal defense of public services and social rights against the crisis and Spanish sovereign debt. These five features have not only expanded and strengthened the movement, they also infected other collectives that have assumed part of the vocabulary and organization of the 15M Movement. For example, the Mareas Públicas (Public Tides), workers associations in defense of the different public services in Spain: education (Green Tide), health care (White Tide), social services (Orange Tide), civil servants (Black Tide) or feminists in defense of the rights of women (Purple Tide). The ‘tides’- thanks to the transversal logic of the 15M Movement – surpassed the trade unions’ sectoral interests, linking the defense of dignified labor with the defense of universal social rights.

1. Questions for the 15M Movement: innovation, organization, actors and limits of the Spanish Revolution

Two years have passed from the beginning of the 15M Movement and the protest is still alive. In terms of duration and perseverance, the movement has defied its critics. At the same time, the 15M Movement is now dealing with different challenges and problems. Many things changed between 2011 and 2013. We have focused our working hypotheses on two different aspects and through two sets of questions we have tried to evaluate the innovative articulation of the Spanish revolt as much as they try to evaluate its limits:

1) Innovative articulation: What are the radical innovations of the 15M Movement in the organization of social antagonism? What are the contrasts and points of convergence with other classic collective movements? What type of social actors took part in the movement? Can we speak of the rise of new social actors? What is the role of the internet and social media in the diffusion of critical content, information and protest calls? They were essential in the articulation of the movement, but are they the best tools to create a critical common sense in the population (population of different ages, with different levels of education and limited in their access to the internet)? Can they compete with traditional media? the 15M Movement has introduced discursive changes in the protest culture thanks to its own vocabulary and political grammar, but are these social changes affecting the official institutions, major parties and trade unions? Is there any translation of the demands of the 15M Movement into the political structure of the state?

2) Limits: the PP (Popular Party) have implemented the austerity measures with more authoritarian means than the former government (constant use of police force, arbitrary identifications, preventive arrests, anti-democratic discourses, racism, etc.) destroying all the rights and social gains made by the popular classes. The whole machinery of the state has been used to dispossess the working classes and citizens in terms of even the most basic resources. In this aggressive context – inspired by the fascist past of the Spanish extreme right – we can ask ourselves whether assemblies are the best way to organize dissent or whether we might have to test new forms of institutionalization (hybrid forms). Is the movement in need of political representation? Does the 15M Movement need to become a party or a platform and enter into the logic of electoral politics? Would this not mean a betrayal of its assembly dynamics? How much longer will the protests be able to occupy the streets with the same level of organization? Are these antagonistic dynamics enough to widen and strengthen the bonds within the movement (or to attract new potential militants)? Or are they reaching an impasse now? In conclusion, is the movement reaching its long-term targets, is it using adequate means?

2. Methodology

1) Sources: we have analyzed a vast amount of articles (newspapers, documents produced by the movement, analysis, critiques, etc.), images, videos and data in order to have a well-founded understanding of the 15M Movement from different perspectives. It was important for us to understand the 15M Movement from within as much as from the outside: on the one hand, we have investigated what the movement has said about itself and its own dynamics and, on the other hand, the things individuals, parties, trade unions, media and opponents have said and thought about the Indignados.

2) Participant Observation: as activists, we have participated in many assemblies of the 15M Movement and are working on several tasks. Our understanding of the socio-political phenomenon of the Indignados is immediate – we are participants – and, simultaneously, reflexive: we have cooperated (and we are still cooperating) with assemblies to put projects into practice, prepare demonstrations or debates about politics and social themes. Although the assemblies are truly democratic, horizontal and deliberative (all people can talk, all people can decide), they are not exempt from power relations. In our presentation, we will try to point out the difficulties and virtues we have encountered in the assemblies.

3) Assemblies Poll: we have sent a poll with 26 items to the assemblies of the 15M Movement in Madrid. Later we will try to reach the principal provinces of Spain. We expect to have some interesting results to share in the workshops, since the poll tries to create a general profile of the activists and the assemblies, and of the projects they are currently working on.